Chemical Hazards in Food: The European Union Takes Stock

The European Union (EU) is the biggest importer and exporter of agricultural and food products in the world. Thirteen percent of foods consumed in the region are imported. The EU is also regarded as one of the regions with the most comprehensive food safety regulation and enforcement models. Yet there are still shortcomings. In a report released this week, the European Court of Auditors detailed its review of the EU’s system in addressing chemical hazards found in food and agriculture. Chemical hazards are one of three primary categories of food hazards, in addition to physical and biological hazards.

Laboratory testing is a fundamental part of the procedures used to formulate food safety specifications and, thus, regulations, as well as monitor food safety and conduct enforcement. Although the report covers shortcomings in the legal structure, legislative progress and implementation of the EU’s regulations around chemical hazards in food, this blog focuses on the report’s findings that most directly impact lab testing for chemical hazards in food.

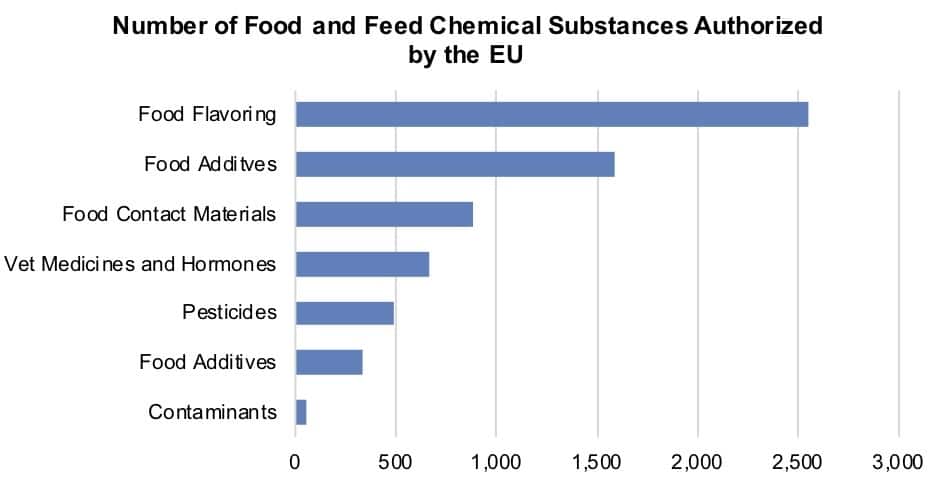

The sources of chemical hazards regulated in food sold in the EU span the food chain, from the farm through processing to final sale. The four types of chemical hazards covered in the report are food ingredients (additives, enzymes flavorings, nutrient supplements), food chain residues (feed additives, veterinary medicines, pesticides), contaminants (environmental pollutants, natural contaminants, process contaminants) and food contact materials.

Although food chemical hazard regulations are largely written at the EU level, member states are charged with enforcement while businesses shoulder the primary responsibility for compliance. As part of enforcement, member states conduct inspections, checks, and in some case sample testing. However, member states vary in their levels of enforcement, often due to a lack of resources, which impacts control activities, including testing.

The report also highlights how EU food legislation on chemical hazards remains incomplete within certain categories of chemical hazards, specifically, additives, enzymes, flavorings, nutrient sources and pesticides. In addition, the EU’s progress in addressing each type of chemical hazards is uneven. For example, legislation is more complete for pesticide residues and veterinary medicines than for enzymes and food contact materials. Even for these more heavily regulated chemical hazards, members states cannot keep up with the monitoring requirement due to a lack of resources.

Further, more testing will be required, as the European Food Safety Authority, the EU’s source of scientific information regarding food, works to decrease the backlog of chemical hazard evaluations, including testing, necessary to complete legislative proposals. For example, safety assessments have only been conducted on 18 of the 281 food enzymes for which they are required. Such evaluations also include re-assessments, updates to methodology and determination of tolerance levels.

Food imported from outside the EU presents its own set of safety challenges. The report found that although foods of non-animal origin made up 59% of EU food imports in 2016, they are typically checked for chemical hazards less often than feed, fats and oil, and food of animal origin. Controls have grown for certain categories of food of non-animal origin, such as contaminants, pesticide residues and food additives. In fact, such controls now cover 35 products and 24 countries outside the EU.

Nonetheless, even within these categories of chemical hazards, monitoring is uneven. While physical checks, which may involve lab tests, of food of non-animal origin are more likely in the case of pesticide residues and contaminants, they are less likely for food flavoring, enzymes and supplements. For animal-origin food, checks for additives are less common.

Among the report’s recommendations that could lead to more testing is updated food chemical hazard regulations, more equitable monitoring of pesticide residues in food imported from outside the EU compared to from within the EU, improved enforcement guidance to members states, and enhanced monitoring in general.