Government Funding of CRISPR Research and Policy Changes

The impact of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system has been widely documented. The simple and cost effective technique is a precise and rapid method for DNA modification. A new report from the US Congressional Research Service (CRS) highlights the scientific and ethical implications of the technique, particularly in light of its use to modify human genetic traits that may be inherited. In particular, the report provides insight into the federal government’s funding of CRISPR research and changes in its current regulatory policies surrounding the technology.

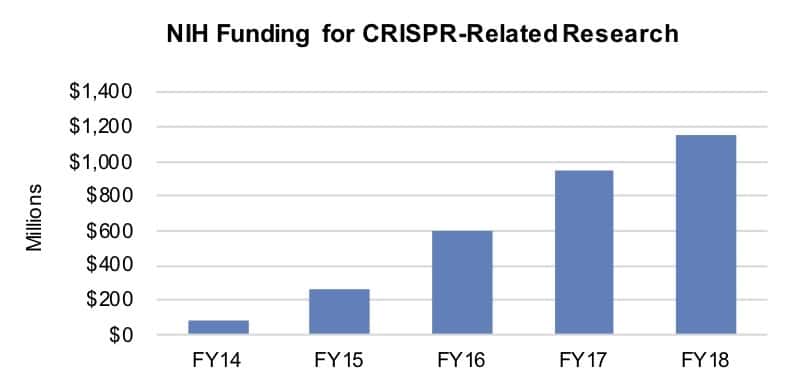

The rise in NIH funding of research related to CRISPR has been swift, with spending on 6,685 projects totaling $3,083.4 million between fiscal year (FY) 2011 and FY18. At its high point, between FY14 and FY15, funding jumped 213.1%. Such funding surpassed $1 billion for the first time last FY to reach $1,155.4 million as the result of an 21.9% year-over-year increase.

Source: CRS

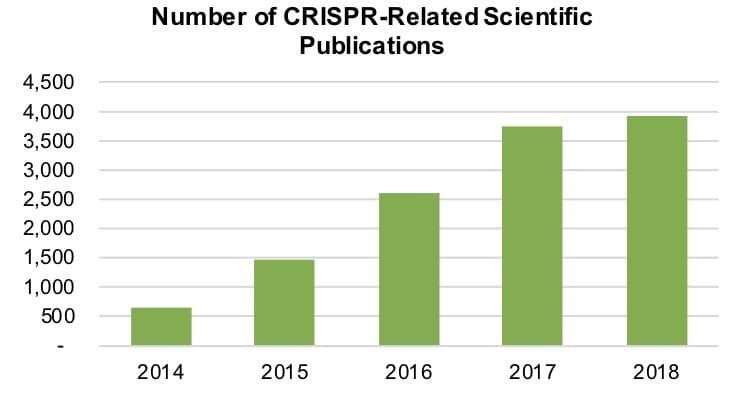

The number of CRISPR-related publications, as measured by listings in the SCOPUS database of peer-reviewed research, reflects the rise in funding. Between 2015 and 2016, the number of such publications grew 117.5% to 1,457. This year, the number topped 3,900, increasing 4.8%. In total, 12,900 papers related to the technique have been published since 2011.

The debate around guidelines for CRISPR research, as well as restrictions on what type of research can be funded, has increased as the full potential of CRISPR gene editing has become clearer. Public, private and nonprofit interests are investing in the technology to treat disease, improve crop production and create new sources of energy, for example. But many observers caution that the process of making these genetic changes and the extent of their potential effects is poorly understood.

The federal government’s response to these increasing concerns has included studies and commissions, but is still largely guided by existing policies. One of the most significant federal government mechanisms for overseeing genetic modification is the 1986 Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology. It states that the regulation of any genetically engineered product should be accessed based on the product itself and its applications, rather than the method used to produce it. Consequently, regulations specifically focusing on CRISPR were not considered necessary, although agencies were urged to examine and update their approaches in light of scientific developments.

Indeed, federal agencies have begun to address new gene editing options, specifically CRISPR, through their own set of guidelines, requirements and policies. Due to its amount of funding for CRISPR-related research, the NIH has been at the forefront of addressing CRISPR research guidelines. Responding to what maybe the most contentious concerns regarding such research, the NIH has always restricted the use of its funding for creating or working with any genetically engineered human embryos.

However, research involving the transfer of genetically engineered recombinant nucleic acid molecules (combined DNA from different sources), which can be accomplished with CRISPR, into human research subjects is eligible for funding clinical research trials of gene therapies, for example. But such transfers cannot involve germline changes (potentially heritable changes), and they must be registered, receive prior approval and meet certain reporting requirements.

Recent developments noted in the CRS report suggest that changes are underway in this area. An NIH proposal released last year would loosen the requirements for using recombinant nucleic acid molecules in human research, removing many of the special approvals and oversight required. The proposal argues that gene therapy trials no longer require special treatment because the technology is now more routine. Submissions of new gene transfer protocols have been put on hold pending finalization of the new guidelines.

Changes in how CRISPR is viewed are also evident at the FDA, although it still maintains restrictions on human embryo germline modifications. Because gene therapy is considered a biologic drug, an investigational new drug (IND) application using genetic modification techniques must be accepted by the FDA before beginning the clinical studies needed for the treatment’s approval and subsequent sale. In a first for the Administration, last fall, the FDA approved two clinical trials involving CRISPR-Cas9-based treatments: CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex’s ex vivo gene therapy for sickle cell disease, and Editas Medicine’s in vivo treatment for inherited retinal degenerative disorders. The FDA is also preparing new policies for addressing CRISPR, and genetic alterations in general, in animals used as food products. In 2019, the Administration plans to release a guidance document for genetically modified animals used in research or as food.

And when the modified animal, such as a mosquito, is not classified as food but as a pesticide, the EPA is charged with making the regulatory decisions. For example, the EPA would be called upon to regulate a modified organism released into the environment as a means of insect population control. The report did not indicate whether the EPA has directly addressed these types of CRISPR modifications yet.

Likewise, the Department of Agriculture has not explicitly stated new policies for the latest generation of gene editing techniques. However, the Department did issue a clarification last year. The Department stated that CRISPR alternation would not be treated any differently from other traditional gene alteration technique, excluding the alteration of plant pests.